All Disease is Local

Just like Politics, all Disease is Local

By any measure of compassion or enlightened self-interest, Americans should be more interested in malaria than Zika. We should see malaria as a threat to global security, where disease incidence of this magnitude contributes to governmental fragility and regime insecurity. We should see malaria as a serious impediment to global economic growth and overall prosperity. And we should see malaria as a deadly and crippling disease that demands more of our compassion and more of our aid to treat and eliminate it.

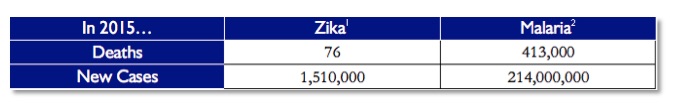

This stark comparison for 2015 should be enough to shift our concern from Zika to malaria:

…but it has not, even with a disparity of roughly 150:1 in cases and 5,000:1 in deaths. But as note 1 below explains, these figures may be serious underestimates. Imagine then that they are off by a full order of magnitude, that there were 760 deaths and 15 million new cases. Even then, you would think malaria would receive more attention.

However this diagram from Google Trends shows that in America Zika (in red) has been far more frequently searched than malaria (in blue) all throughout 2016:

The graph, not surprisingly, is essentially inverted for countries like Uganda, Nigeria, Kenya, Mozambique, Tanzania, Pakistan, etc. Take a look at https://www.google.com/trends/. Of course interest-in, as evinced in Google searches, is not synonymous with caring-about, but absent some other measure, it’s not a bad proxy.

So why are Americans more interested in Zika than malaria? Here are seven possible reasons.

Seven Reasons

1. Spread. Much of the news about Zika is concerned with the potential for it to spread to new and larger geographic areas. And while WHO and others say that “about 3.2 billion people – nearly half of the world's population – are at risk of malaria” [ 3 ], the only area that has seen a recent increase in the incidence of malaria (2000 – 2015) is Venezuela [ 4 ]. So the spread of malaria does not seem to be as significant a concern as the potential spread of Zika –to Florida, to Texas, etc. In the US, news often focuses on tracking incremental change; witness the daily and even hourly obsession in reporting polling results in this year’s presidential election. And so it is with the spread of Zika.

2. New. Whatever is new tends to grab and hold our attention more than what is already known. For most of us, malaria is associated with the building of the Panama Canal over a hundred years ago. Zika, though discovered in 1947, has only been in the news since last year. Malaria is old news – Zika is new.

3. Visualization. Victims of malaria are typically shown lying down and listless, with no visible symptoms other than extreme fatigue. Zika on the other hand can be encapsulated in a single image of an infant with microcephaly. Photographs of these children are heart-wrenching and unforgettable in a way that pictures of malaria victims often are not.

4. Threat to Children. There’s no evidence that I’m aware of that suggests that either Zika or malaria selectively targets children. Though it is not as widely known, fetuses can be infected with malaria just as they can be from Zika. [ 5 ] But again because of the cases of microcephaly, the perception is that children are particularly vulnerable to Zika.

5. Control. Americans like to be in control, or at least to believe that they are in control, of their lives. Indeed, some of the election polling in the last year suggests that a sense of a lack of control in terms of employment and economic advancement is at the heart of the anger and frustration expressed by voters. Malaria, for Americans, is under control. As the CDC says, “Malaria was eliminated from the United States in the early 1950's.” [ 6 ] But with no vaccine for Zika, we’re left with exhortations to remove standing water and wear insect repellant. In effect we’re protecting against, but not controlling for, Zika. For us, it is literally out of control.

6. Personal Risk. Related to control is the threat that we are personally and individually at risk to acquire Zika, whereas, from our perspective, it is “others” who are at risk of contracting malaria. And being human, we are naturally, if sometimes unfortunately, more concerned with our own well-being than that of those others.

7. Sexual Transmission. Zika, unlike malaria, can be spread through sexual contact. In many ways, Americans have yet to fully disentangle HIV/AIDS from sex, and now with documented cases of sexual transmission of Zika, these mixed feelings are being stirred again. Blaming mosquitoes is easier than blaming ourselves.

Observations

Not just for Zika and malaria, and not just in America, it seems likely that most people see all disease as local, that they are most interested in what they feel is most threatening to them personally, and that some combination of the seven reasons above animate these feelings.

Conversely, these seven reasons can be seen as the obstacles that must be overcome in prosecuting a campaign or raising support for fighting a non-local disease. For example, generating support in America to fight malaria.

Notes

[ 1 ] Unlike malaria, there does not seem to be a single, reliable source for global Zika statistics. The closest I have been able to find is this Zika Situation Report from WHO: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204348/1/zikasitrep_5Feb2016_eng.pdf In the aggregate, it documents 1,510,079 cases and 76 deaths over roughly the year 2015. But because Zika infections are often asymptomatic and because Zika awareness was only beginning to grow in 2015, and early deaths may not have been attributed to the disease, I’m certain these numbers represent a serious underreporting.

[ 2 ] http://www.who.int/malaria/media/world-malaria-report-2015/en/

[ 4 ] http://www.who.int/gho/malaria/malaria_003.jpg?ua=1

[ 5 ] http://www.who.int/malaria/areas/high_risk_groups/pregnancy/en/

[ 6 ] https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/facts.html